Art Education

Site Projects Inc. commissions internationally recognized artists to create temporary and permanent visual art in New Haven's public spaces.

Our work activates spaces not typically associated with art in order to engage the community and to build new audiences for art. Each art commission is highlighted by educational programming and community-wide social events. We provide educational resources and programming to the community we exist in.

“Public Art Fellows 2019”

Public Art Fellows (PAF) is a six-week paid summer fellowship that encourages young artists (grades 9-12), to engage the city as a landscape filled with possibilities for artistic expression. Each program is led by a team of artist-mentors who guide fellows through the creation of works responsive to sites and artworks that celebrate public art in the City.

The PAF’19 educational program, Video Arts Boot Camp, invited the fellows to use their video talents to create work ranging from documentary to conceptual installations. Fellows explored downtown New Haven, interacting with public art and developing a video program that engaged the history of transportation in the city: its rivers, roads, and railways. In addition to local video artist mentors, visiting professionals discussed their own art practice, and helped fellows develop their work to new levels. A community celebration in September showcased their video installations and all the work these talented young artists created during the summer.

Click here to see what our PAFers have been up to this summer!

“Public Art Fellows 2018”

Public Art Fellows (PAF) is a five-week paid summer fellowship that encourages young artists (grades 10-12), to engage the city as a landscape filled with possibilities for artistic expression. Each program is led by a nationally recognized artist and a team of artist-mentor(s) who guide fellows through the creation of works responsive to sites and artworks that celebrate public art in the city.

The PAF’18 educational program, Cartoons + Comics, invited fellows to use their cartooning talents to tell a story. Fellows toured downtown New Haven, exploring public art and developing a story that engaged a favorite artwork or several artworks in the city. In addition to a local cartooning artist-mentor, a digital comic book artist-mentor discussed the art of developing exciting narratives that keep the pages turning. A community celebration in August showcased the comic books of these young talented artists.

Click here to see the complete Comic Anthology created by the PAF’18 cohort!

Site Projects would like to thank the following for making PAF'18 possible:

Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects

NewAlliance Foundation

All of the generous donors who supported us through this year's Great Give

Click here to see what we did with PAF'17

““This gave me confidence in my ability. I feel like I can call myself an artist now.”

Destiny Jones, PAF’17

”

““From a young teen’s developing point-of-view, this increases one’s understanding that possibilities can take place anywhere. This is a powerful experience. What you do is wonderful. Thank you.”

Marta Violette

”

“Programs”

Art Sites New Haven Public Art Audio TOur

Public art is a vital and revitalizing part of New Haven’s urban landscape, but often the stories, authors, and origins of these works are lost or forgotten. ArtSitesNewHaven.com illustrates, locates, and describes public art throughout the city.

Autumn Morrair, New Light HS '16

Site Projects, in partnership with WNHH, New Haven Independent Radio Station will now create a complimentary public art audio tour with New Haven high school students.

ArtSites offers tourists and residents, students and teachers an essential tool to learn of the remarkable history, outstanding artists, and visionary leaders who have fundamentally shaped the public arena in New Haven.

Participating students will be actively involved in the expansion of this valuable community resource. The audio tour will further facilitate self-guided tours and students will have the opportunity to become the spokespeople for our city and for our culture.

The program began in May 2016 with our inaugural presenter from New Light High School. Beginning in full force in Fall 2016, this six-week audio tour program will occur twice annually.

In addition to being published on ArtSitesNewHaven.com + SiteProjects.org, audio segments will be broadcasted on WNHH.

Interested in participating? Contact Liz Antle-O'Donnell, Program + Outreach Manager

“Teacher Workshop”

On March 1, 2013, 16 specially selected teachers, representing 12 New Haven schools, attended a meeting with Site Projects. Their task was to brainstorm the integration of Site Projects' 2013 public art project with their current curricula. Immediately following the workshop, teachers began developing their own ideas. Local educators and aspiring teachers have begun to embrace the idea of integrating the artwork into their lessons with an enthusiasm that proves the importance of art in education. Check out the video below!

“Lesson Plans + Educational Guides”

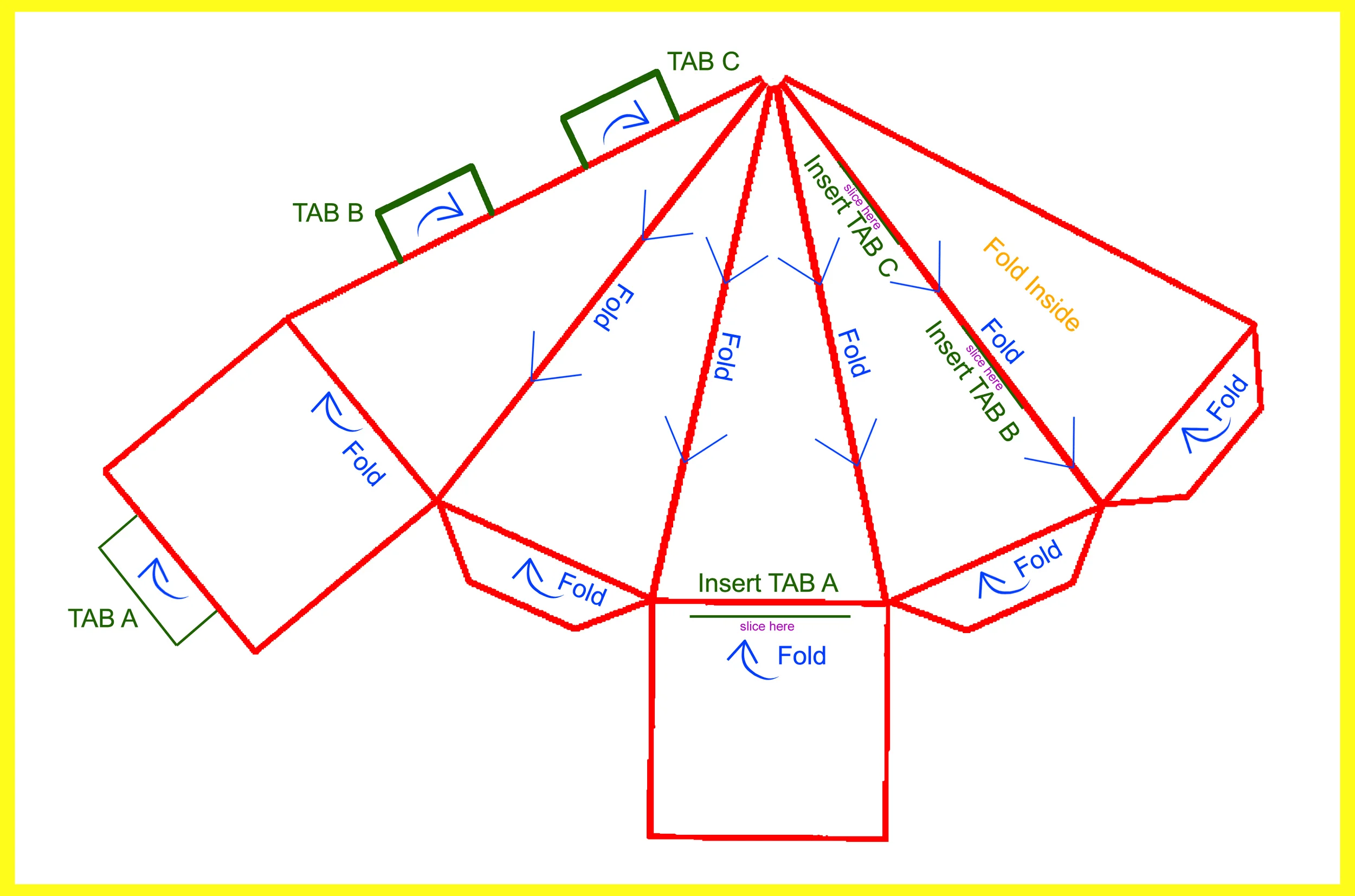

“Folding Exercises”

FOLDING EXERCISE 1 - Night Rainbow | Global Rainbow New Haven

Click on the images below to save or print them. Enjoy!

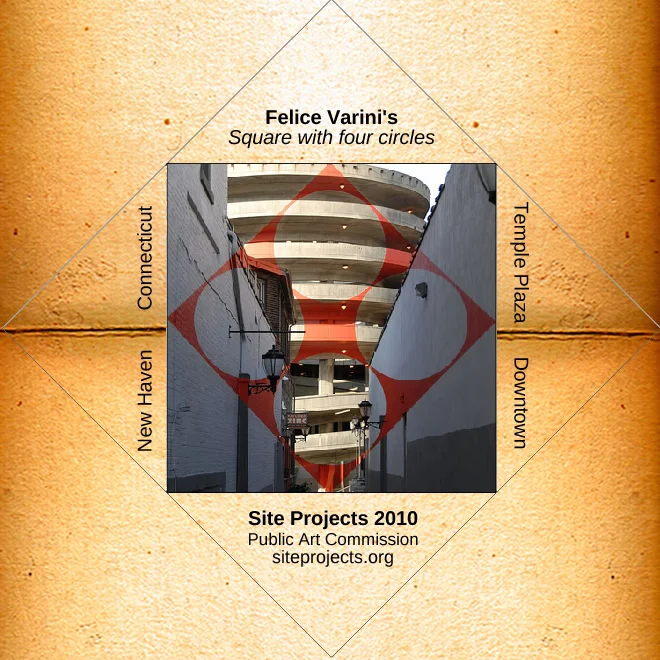

FOLDING EXERCISE 2 - Square with four circles

Click on the images below to save or print them. Enjoy!

“Commentary”

+The Trumble Diaries: Matej Andraž Vogrinčič by Senior Curator of Paintings and Sculpture at the Yale Center for British Art Angus Trumble

What is this work of art? Is it a very large sculpture, a piece of landscape architecture, or civic design? Is it an event, a memory, a 3-dimensional visual poem, or simply a place?

In the short-hand jargon of the current contemporary art world, the work of Slovenian artist, Matej Andraž Vogrinčič is usually called ‘site specific’ or ‘installation’ art. This has developed out of a remarkable transformation in the range and type of locations that artists sought out in the past 50 years. American ‘earthworks’ or ‘land art’ of the 1960s, for example, is one of the most striking of those recent movements. In common with many other kinds of large-scale ‘installation’, these projects, which were sometimes even created for places where few if any people might actually see them, defied the conventions of the modern art market that have arisen over the past 300 years. It is often impossible to ‘own’ an installation, to collect it, or to corral it into a larger collection of art by other people. It insists upon its own autonomy, and frequently takes advantage of unique features of the surroundings, whether it is a stretch of open country or a disused urban space. And the artist asserts his right to shape and determine every aspect of our experience of the work of art. It can never exist in quite the same way anywhere else, or at any other time, except in our memories.

Matej Andraž Vogrinčič has created installations in Ljubljana, the capital City of his native country, Slovenia, as well as in Venice, Italy; Adelaide, South Australia; the isolated opal-mining community of Coober Pedy in the desert of far outback Central Australia; Perth, Western Australia; Christchurch, New Zealand, Liverpool in the north of England, and elsewhere. This installation in New Haven is his first work in the United States.

In each case, Matej Andraz takes advantage of the unique environment in which he works, often alluding to the history of the place, bringing to the task not merely hard physical work, but wry wit, and a no-nonsense, non-argumentative accommodation of the concerns of local people, the requirements of the civic authorities, even the weather. One of the most important features of his work is its capacity to interest and stimulate children, and while his works range widely in format, they have in common a basic clarity in the choice of simple motifs with local resonance, and a capacity to harness those motifs with intelligence, and gentle humor. This text was drafted for public information by a private group of individuals in New Haven, who made possible Matej’s recent, 2007 Farmington Canal ‘Erector Set’ project, part of which is illustrated above. The text, which was aimed at the general public, was used by the group in various ways along with an interview I videotaped with Matej.

+A.C. Gilbert & Memory by William Brown, Eli Whitney Museum

Imagine you are talking to your grandfather about the year when he was your age. Ask him: when you think of New Haven back then, what image comes into your mind? Very likely he will say: I see the bright red steel box of an A.C. Gilbert Erector Set. I see nuts and bolts and girders; I see an electric motor and magnet.

That box was a treasure chest. It was the most famous building toy in the world. All the years that America built its great bridges, and railroads, and skyscrapers, Erector Sets taught young engineers to build and dream. And New Haven built Erector Sets.

The Erector Set was invented by A.C. Gilbert, who came to New Haven in 1904 from all the way across America to study medicine at Yale, to star as an athlete, and to perform magic for audiences in local vaudeville theaters, where before television, movies and radio, people were entertained with music and magic shows. Gilbert loved to perform. He also designed and sold magic tricks and he did it with such success that he never got round to practicing medicine.

One day in 1913 when Gilbert was traveling to his Magic store in New York City on the New Haven Railroad he saw construction everywhere. Electric towers along the tracks would allow new trains to travel underground to a Grand Central Station without the hazardous smoke of the old steam locomotives. Gilbert realized that those steel lattices, girders and the electricity they carried would change everything, and that they could also be made to work on any scale. The result was the miniature construction empire in a box that would make New Haven famous.

Gilbert’s factory and fame grew quickly. He was a gifted salesman. He promised parents that his construction sets were an investment in their child’s future. In 1920, when it became possible to speak on radio waves, he built Connecticut’s first broadcast station and pioneered a whole new way to talk to his customers. His radio tower was a landmark for his Fair Haven factory and for New Haven.

Why is this memory so powerful? An Erector Set was the king of toys when no one had many toys. At it peak, 3000 people worked in Gilbert’s Fair Haven factory. They were proud to be producing an icon of invention. But most important, Gilbert built a powerful message into the parts and tools he shipped round the world. Each Erector Set said: I believe you can teach yourself to solve any problem. It was a message, broadcast from New Haven, that inspired three generations.

William Brown is Director of the Eli Whitney Museum in Hamden, CT and a noted A.C. Gilbert scholar. He is author of The Gilbert Epoch, in Essays in Arts and Sciences, Vol. XXV (University of New Haven, 1996). He has produced exhibitions on Eli Whitney, A.C. Gilbert and Leonardo daVinci that explore the balance between classroom and workshop learning. Under his direction the Museum's experimental building workshops have grown to produce 72,000 learning projects a year. His work has been recognized by two honorary degrees.

+A Short History of the Farmington Canal by the New Haven Museum and Historical Society

A canal is a man-made waterway used primarily as a passage for boats and ships where there were no navigable rivers. Canals have been used since ancient times but only grew popular in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. In the New World as people began moving inland, it was important to find new ways to ship food and wood out of rural areas into the cities, and ship much-needed supplies back.

In the 1820s people felt that New Haven, with its busy harbor, should have a canal to connect it to towns further inland. Many New Haven residents were excited about the prospect of linking New Haven to Massachusetts with the canal to be named for the source of its water, the Farmington River. As with highway construction today, the excitement wasn't shared by everyone, but the project began in 1822.

The biggest problem facing the builders of the canal was getting the money to pay for it, which took over 2 years. Finally, on the 4th of July, 1825, a ground breaking ceremony was held in Salmon Brook, Connecticut, and the work got under way.

Canal construction in America faced many problems. The first canal builders in America were amateurs, and they made many mistakes. The Farmington Canal was also not built by one company, but was contracted out to local companies, each working on separate sections. These companies usually hired family and friends to do the digging, but when this didn’t supply them with enough workers, they hired free African Americans and Irish immigrants.

In 1825, without mechanical equipment, digging the canal was very hard work. Laborers used axes, shovels and wheelbarrows to move the trees and dirt. They worked all day long, for a dollar a day, and then walked home.

The canal was opened in 1828 but it was not a financial success. The money collected from tolls and other fees was barely enough to pay for its maintenance. However, not long after the canal was built, railroad companies began looking for a place to lay railroad tracks and the canal pathway was an attractive possibility. In 1846, speculators got permission to replace the canal with a railway line. Trains ran along the old canal path from 1848 until the twentieth century, when the path was converted into trails for public use.

Amy Trout is Curator of the New Haven Museum and Historical Society (where she curated the 1995 exhibit on the Farmington Canal), and is the author of The Story of the Farmington Canal (The New Haven Colony & Historical Society, 1995). This essay was excerpted from Ms. Trout’s book by Benjamin Breton, Museum Teacher at the New Haven Museum and Historical Society.

+The Farmington Canal in the Urban Landscape by Alan J. Plattus, Professor of Architecture, Yale University

At more than 350 years old and counting – not to mention its history before European settlement – the city of New Haven is old by North American standards and exceptionally rich in layers of physical history.

In the center of New Haven there is the strong and clear pattern of the nine-square grid of streets laid down in 1638 by its founders -- inspired by the Bible and descriptions of the geometrically ordered Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. This regular grid provides a framework against which earlier and later features can be read. Among the more dramatic of those later features is the bold diagonal gash across the eastern corner of the nine squares: the path of the Farmington Canal. The Canal originally terminated in the Canal Basin in New Haven's harbor. From there it ran north over 80 miles to join the Connecticut River at Northampton, Massachusetts. Like the old turnpikes connecting the city to neighboring settlements, the Canal was part of a radial system spreading out from the tightly ordered center and reaching into the surrounding countryside.

Laid out in 1825 as an ambitious effort to re-situate New Haven economically and geographically, the Farmington Canal functioned as an active means of water-based transport for barely twenty years, but it has had a long and fascinating afterlife -- converted first to an important rail corridor, then largely abandoned and most recently, as a piece of a growing network of local, regional and national trails that may eventually connect the entire east coast for bicyclists and pedestrians.

And yet, even today its obvious links to the past are still fascinating. It’s an excavation into New Haven’s history. While there is little along its route dating to the1820’s, it provides a vantage point on the changing city and reveals traces of almost every subsequent era of New Haven history, as well as a good deal of environmental history. The portion of the old canal corridor in the heart of New Haven, between Prospect and State Streets, is literally an archaeological excavation. At the Whitney Avenue crossing one looks up to the old McLagon Foundry building, from the 1870’s, a reminder of how the Canal and the subsequent railway were a conduit for industrial development from the center of the city to the sprawling Winchester Repeating Arms factory (now Science Park) in Newhallville. And at Grove Street one can see a veritable cross-section of historic masonry buttressing the walls of the corridor.

In its new role as a piece of recycled industrial history the canal returns in certain respects to its origins. Much as it played its role in the rise of urban areas as industrial centers served by canals and railroads, it is now a harbinger of a new age for New Haven and American cities as social, cultural and recreational centers. In this city the canal corridor continues to derive its meaning from its unique difference –its difference of level, of orientation, of scale and of pace – raising questions and continuing possibilities for exploration and discovery.

+Water to Rails: Industrial Growth in New Haven by Professor Douglas Rae, Yale University School of Management

In 1800, when the U.S.A. was still a teen-aged nation, shipping things like food and lumber was slow and costly. For example, shipping the oats for your morning porridge took as long and cost as much as it had when people like Julius Caesar or Queen Boadicea were impatiently waiting to eat breakfast. This meant that almost everything people used—the things they ate, wore, or built with-- had to be produced within about 20 miles of their homes. Only things that were small and very high priced, like jewelry, spices, or coins could be transported over long distances at costs that made sense – and even then the prices of such things made sense only to the rich.

When the Farmington Canal was completed, it became possible to ship heavy items to New Haven cheaper and faster than had been possible before. By 1830, four million pounds of goods were shipped between New Haven and Northampton, Massachusetts, and the 75-mile trip could be covered in just one day. It was one of a number of canals constructed to improve America’s links to its developing interior, like the much larger Erie Canal, from Albany to Buffalo in New York State, which in 1825 connected the east coast to farm country in places like Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. Breakfast got better and cheaper because the ingredients were produced in the right places.

But the canals were just a temporary fix. Railroad trains were being pioneered even before the Farmington and Erie canals were dug, and their roll-out in the 1840s was the real revolution. For the first time ever in human history, you could ship breakfast at 50 miles an hour – faster than five times the speed of any canal boat. Heavy and bulky things – corn, oats, lumber, sugar cane, steel bars – could travel from Chicago to New Haven in just a day or so, and could do it cheaply.

However, these canals were obsolete just two decades after they were built. By 1847, the Farmington Canal was drained. Wooden ties and steel rails were laid down and in 1848, the New Haven & Northampton Railroad was up and running along the canal pathway. Even more important, the New York and New Haven Railroad started business the same year, and once New Haven was connected to New York, it was connected to the world!

Smart people made it a center for the manufacture of many of the things the world wanted most. For example, by the 1850s Chauncey Jerome was making the world's best cheap clocks and shipping them all over the USA and even to Europe and Asia. Winchester was making the best rifles in the world and shipping them to the four corners of the globe.

Douglas W. Rae is Ely Professor of Organization and Management at the Yale School of Management. A fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a former Guggenheim Fellow, Professor Rae is frequently consulted by the media for his views on urban development, reversing urban poverty, and regionalization. His latest book, City: Urbanism and Its End, was published in 2003 by Yale University Press.

Audio Transcripts

“The Science of Art: Marvin Chun Lecture”

How does color affect human perception? Yale Professor, Marvin Chun, explored this phenomenon as part of The Science of Art Lecture / Workshop Series for Night Rainbow | Global Rainbow New Haven. Here are some photos from that day.